Diagnostic ultrasound has a wide range of uses in musculoskeletal assessment and guided interventions. Defining competency in musculoskeletal ultrasound is a grey area and very individual to your own caseload and role. For those starting out on ultrasound, there is a lot of research required and new information to consider. However, whatever your role, it is essential that you embark on a structured learning pathway to reach the required standards, to become competent in diagnostic ultrasound.

Musculoskeletal ultrasound was traditionally taught and learnt in radiology departments by radiologists and sonographers. Over the past 15-20 years musculoskeletal ultrasound has been adopted by clinicians outside of the radiology department. Ultrasound is a natural extension to a clinical assessment and is becoming more and more popular with a variety of clinicians. However, there is a distinct lack of information around gaining competency in MSK ultrasound and a lack of standardised learning pathways.

There is currently no agreed competency pathway for all clinicians, be it orthopaedic surgeons, physiotherapists, rheumatologists or sports doctors, to carry out diagnostic ultrasound and also ultrasound guided injections. One reason for this is that the exact use of ultrasound will vary according to the role of the clinician. With the appropriate training diagnostic ultrasound can enhance the care pathway provided to patients by increasing diagnostic accuracy, guiding interventions and reducing patient episodes.

Modular Approach

It has been recommended, by the Faculty Sports & Exercise Medicine (FSEM) and the Royal College of Radiologists (RCR), that you can approach diagnostic ultrasound in a modular fashion. This means breaking down the different areas of the body into regions, such as the shoulder or knee, and learning one joint or one region at a time. The clinician may wish to become proficient in some, but not all of the proposed modules within the syllabus. A modular approach is slightly less daunting for the new sonographer and provides a more manageable learning pathway.

In a past blog post, we discuss formal versus informal learning pathways. A formal learning pathway, such as a postgraduate certificate in musculoskeletal ultrasound, requires you to pass the necessary modules, exams and an OSCE, aswell as completing a clinical placement. This placement involves carrying out 250 scans over a 6-9 month period (150 unsupervised and 100 supervised). However, many people cannot secure a clinical placement and/or a clinical supervisor to complete a postgraduate certificate. Furthermore, if your caseload is limited to a region, such as a shoulder or foot and ankle surgeon, a physiotherapist in an upper limb or shoulder unit or a podiatrist, these courses are less appropriate. Competency is specific to your role, for example, we have had several hip surgeons on our 2 cadaveric ultrasound guided injection course who want to learn ultrasound and ultimately be able carry out ultrasound guided hip injections. The competency pathway must therefore be structured specifically to prove their skills and knowledge to be able to carry out this procedure.

The European Federation of Society’s Role in Medicine and Biology (2008) and the UK Royal College of Radiologist (2005) acknowledged that learning musculoskeletal ultrasound requires around 250-300 scans. This is based on expert opinion and there has been no publications to date that have actually looked at the rates of learning and the competency around this figure. It is important to note that learning a new skill, such as diagnostic ultrasound, is not just about the number of scans that you carry out, but more the quality of teaching and learning opportunities that are available.

Modular based learning can also provide a structure to clinicians such as sports doctors and physiotherapists, who intend on learning all anatomical regions, both upper limb and lower limb. Instead of trying to learn everything at once, which can be quite overwhelming for a beginner, it provides a more ‘bite-size’ approach.

BESS Working Group – Point of Access Shoulder Ultrasound by Shoulder Surgeons

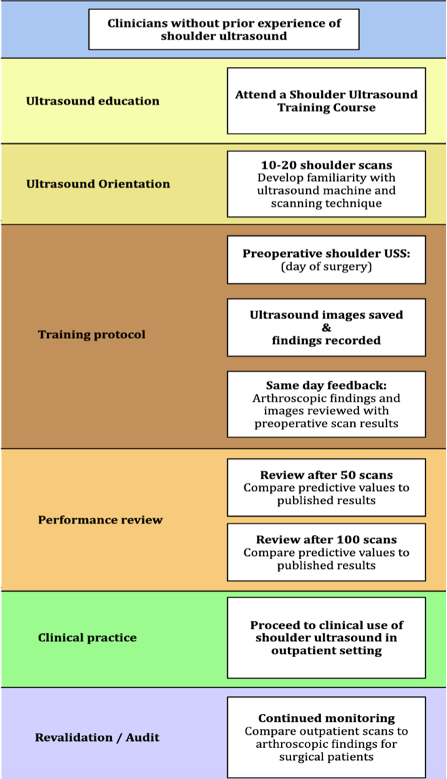

Although it is recommended, there is little evidence or published guidelines on modular based learning in musculoskeletal ultrasound. However, in collaboration with the University of Oxford, the British Elbow and Shoulder Surgeons (BESS), set up a working group to discuss a possible learning pathway and competency based pathway for shoulder surgeons to learn diagnostic ultrasound (see diagram below). The guidance provides a clear module for shoulder surgeons to follow to develop their skills and knowledge to become competent in musculoskeletal ultrasound. This guidance can be adapted to other regions of the body, for example, if you are a podiatrist who wishes to develop their skills and knowledge to prove their competency specifically in the foot and ankle.

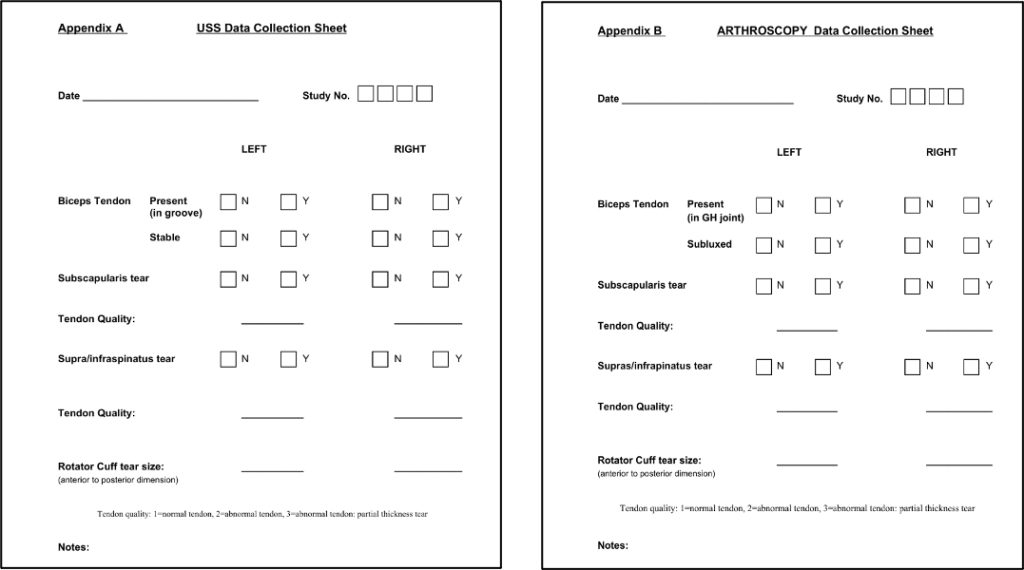

The document and framework was developed by the working group which considered all the current evidence for the use of shoulder ultrasound by radiologists and non-radiologists. It is important to note that shoulder surgeons are in quite a unique group, as they can audit their scans against their surgical findings i.e., carry out a scan before they start the operation and provide immediate, gold standard feedback from their operative findings.

Many clinicians will not have immediate access to surgical findings to audit their scans, other methods can be used to audit scans such as comparing your scan to an expert or against MRI or other imaging modalities.

Essentially BESS recommended an ultrasound training program to allow shoulder surgeons to learn and prove their competency in diagnostic ultrasound of the shoulder. They acknowledge that this potentially has massive cost savings introducing the opportunity of providing a one stop clinic to improve the efficiency and delivery of best care to patients with shoulder pain by reducing the number of appointments required by patients and dependency on MRI, aswell as being able to provide ultrasound guided interventions in clinic.

Diagnostic Accuracy

This provided the data to ascertain their sensitivities and specificities, as well as their predictive values of detecting rotator cuff pathology and long head of biceps issue, which were their main outcome measures. It was discovered that around 50 to 100 scans were necessary for the surgeons to identify the necessary cuff pathology with good sensitivity and specificity. The sensitivity and specificity if the shoulder surgeons were similar to the published results by experienced musculoskeletal radiologists. By 100 scans, these ‘novice’ ultrasonograhers results (sensitivity = 91%, specificity = 97%, positive predictive value = 95% & negative predictive value = 94%) were similar to the very best published results by ‘experienced’ radiologists (sensitivity = 100%, specificity = 91%, positive predictive value = 96% & negative predictive value = 100%).

These guidelines were specifically aimed at shoulder surgeons wishing to learn shoulder ultrasound to diagnose rotator cuff tears and long head of biceps pathology as an extension of their clinical examination. This defines the scope of the competency achieved by the surgeons and the role of ultrasound in their specific setting.

Recommended Learning Pathway

As a result of this, BESS recommended that the following method of training for surgeons was a suitable approach.

Maintaining Skills and Competency

We must remember competency is the bare minimum required for acceptability. Whereas we must all strive for proficiency. Proficiency carries with it a level of mastery that is above the minimum. This will require continued learning and a re-audit every two to three years to continually develop your skill levels and accuracy of scans. Without this then any clinician, quite rightly, will be open to challenge.

Conclusion

This is just one approach to helping prove your competency in musculoskeletal ultrasound. The modular based approach provides a well-structured, achievable approach. For example, if you are a physiotherapist or a sports doctor who wishes to eventually gain competency in all regions of the body, that you may start for the first 3-6 months to concentrate on the region(s) that you assess and treat regularly e.g. shoulder and knee. Once you have developed the skills and knowledge for these regions (and logged the required scans) you can progress to other regions, for example, the ankle and elbow. This process continues to other regions as time progresses and your skills develop.

Certainly, if you want to prove your competency in a specific region, for example, if are a podiatrist or a shoulder specialist/surgeon, then a modular based learning approach provides a clear, focussed structure you can use this structure to prove your competency in musculoskeletal ultrasound.

Follow this link for more information on getting started in MSK Ultrasound

If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact me via email on chris@utrasoundtraining.co.uk.

Further reading:

Faculty of Sport and Exercise Medicine UK’s Ultrasound Guidelines here.

Valentin, L., European Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology.