Musculoskeletal ultrasound has emerged as a valuable diagnostic tool in the field of musculoskeletal and sports medicine. Its non-invasive nature, real-time imaging capabilities, and ability to assess soft tissue structures at the point of care make it a preferred modality for evaluating musculoskeletal conditions (Romero-Morales et al., 2021). With the increasing utilisation of musculoskeletal ultrasound, ensuring the competence and proficiency of practitioners becomes paramount (Messina et al., 2017). To set standards it is important for each specialty to define minimum requirements for equipment, education, training and maintenance of skills (Nielsen et al., 2021). Postgraduate certification programs in musculoskeletal ultrasound aim to enhance clinical skills, promote standardised practice, and improve patient care outcomes (Neubauer et al., 2023). Encouraging students to engage in reflective practice can improve clinical competency, especially when this is supported by peer and faculty feedback.

In healthcare, audit is used as a tool to review the quality of care being provided and whether this is in line with current guidelines and standards (NHS England, 2023).

The musculoskeletal ultrasound in clinical practice audit aims to provide an objective assessment of the practitioner's proficiency in musculoskeletal ultrasound at postgraduate level, identify areas for improvement, and facilitate reflective practice to enhance the quality of clinical care and patient outcomes (Moore and Reeve, 2022).

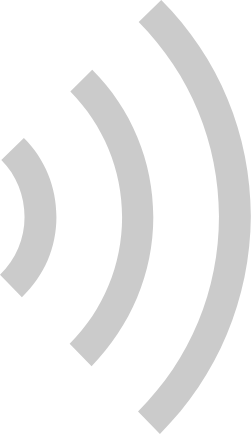

Model of audit used is based on National Institute of Clinical Excellence publication “Best Principles in Clinical Audit” and the presented audit structure provides a practical link between the business of clinical governance, professional self-regulation and lifelong learning (NICE, 2002).

Figure 1: Clinical Audit Cycle. Source: (NICE, 2002)

Audit Objective

The objective of this audit is to assess the proficiency and competence of a postgraduate-level musculoskeletal ultrasound practitioner through a reflective analysis of 150 unsupervised scans. The aim is to evaluate the quality of scans, identify areas of improvement, and reflect on the impact of the postgraduate training program on clinical practice.

Audit Preparation

The images were obtained using GE Loqiq - E next generation portable ultrasound system using GE L4-12t-RS linear transducer at practitioners workplace. Depth, frequency and focal point were adjusted depending on the structure of interest.

Figure 2. GE Loqiq - E portable ultrasound system and GE L4-12t-RS linear transducer.

|

|

Selection Criteria

Scan Selection and Sample Size

A total of 150 unsupervised musculoskeletal ultrasound scans obtained between 10. January 2023 and 25. May 2023 were included.

The scans were purposefully chosen to cover a range of anatomical regions and diagnostic indications to ensure representation of the practitioner's diverse caseload.

Data Collection Process

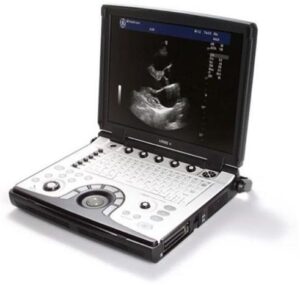

Data was collected by reviewing the ultrasound images, reports, and relevant patient information from the scan logbook with 4 clinical supervisors to ensure impartiality and accuracy and an agreement score was obtained.

Audit Criteria

The audit criteria based on the expected standards of musculoskeletal ultrasound practice at the postgraduate level (Level 7).

The criteria includes:

Data Analysis

Each scan was evaluated against the defined audit criteria and was given an agreement score. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the results to help identify trends.

Reflective analysis was conducted by the practitioner to identify areas of strength and areas for improvement based on the findings, to include personal insights, challenges faced, lessons learned, and plan of action to enhance clinical practice.

Ethical Considerations

Confidentiality and patient anonymity was strictly maintained during data collection and analysis. Workplace requirements regarding data protection and informed consent were observed throughout the data collection process.

Limitations

The quality of ultrasound images may have been compromised due to the lack of operator experience and technical limitations of the equipment used.

Post auditing improvements can be multifaceted, particularly in enhancing diagnostic accuracy and clinical integration. One key area of improvement is the increased utilisation of hands-on training sessions and continued development of curriculum based practices in musculoskeletal ultrasound (Neubauer et al., 2023). Implementing changes based on clinical audit findings can lead to significant advancements in healthcare delivery as well as patient experience. The action plan for making improvements should be:

Fostering a culture of continuous improvement within the workplace and among the profession, where feedback, peer reviews and suggestions are encouraged can contribute towards long term sustainability (Halligan and Donaldson, 2001). The clinical audit cycle is not complete until evidence has been obtained to show that compliance with standards has improved (HCQP, 2020). In this scenario, the learning needs were identified and action taken by undertaking additional research and self-directed study to meet the action plan, set out as above, and further objective activities have been proposed.

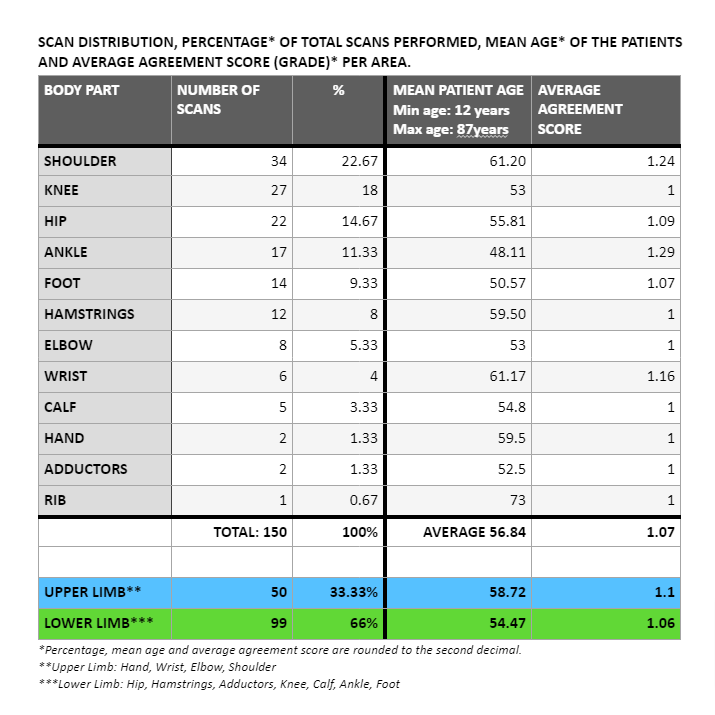

Below is the revised quantitative statistical analysis of the unsupervised scans. The dataset consists of 150 unsupervised scans.

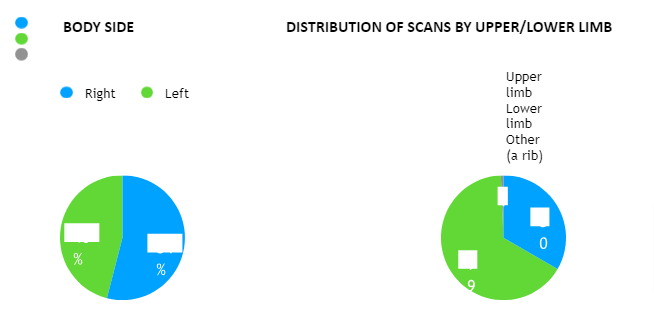

The data includes both left (46%) and right (54%) body sides. The distribution seems relatively balanced, although further analysis would be required to determine any significant patterns.

The ages of the patients range from 12 to 87. The distribution appears to be spread out, indicating a wide range of age groups included in the audit. Out of 150 scans, 10 (6.67%) were normal showing no pathology.

The distribution of body parts is diverse, with some parts being more frequently scanned than others, reflecting the case load of the practitioner- a majority (66%) involving lower limb and slightly above third (33.33%) upper limb. The average agreement scores were 1.06 and 1.1 respectively with 1 being the desired grade to achieve complete agreement between the student and the clinical supervisors.

X-ray was obtained in three cases following the ultrasound scan, of those two results confirming the fracture of the greater tubercle of the humerus and one case showing no abnormality and was further referred to MRI.

MRI was obtained on four cases -one to confirm peroneus longus rupture, another to confirm the complete rupture of the conjoint hamstring tendon and the third following a left shoulder dislocation to evaluate the labrum. MRI concluded the findings of ultrasounds on three occasions, as well as making an additional comment on intra articular structures in the latter referral.

There was a significant discrepancy in one presenting case between the MRI and US finding, resulting in grade 3 agreement score, and this will be discussed in more detail.

For two of the cases evaluated with ultrasound , the patients had obtained the MRI scan prior to attending the student clinic, which helped correlating the findings of the MRI to the ultrasound scan.

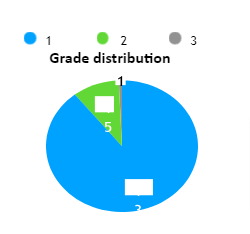

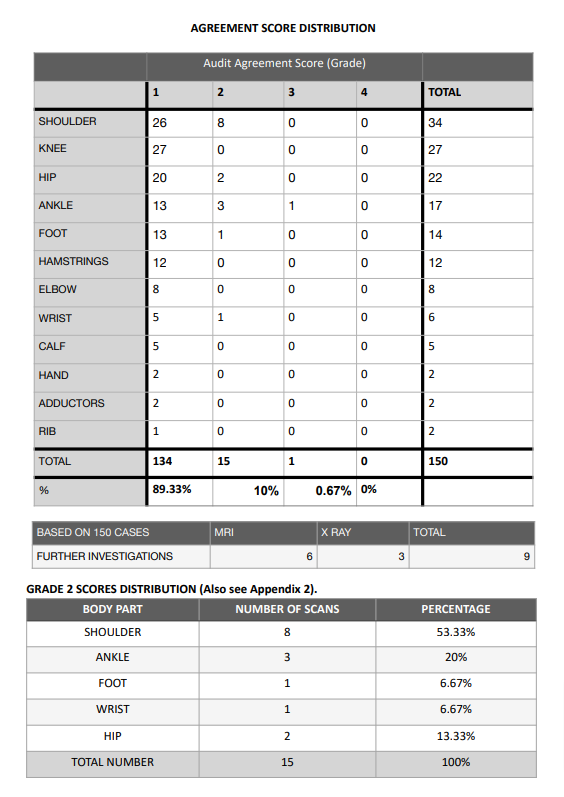

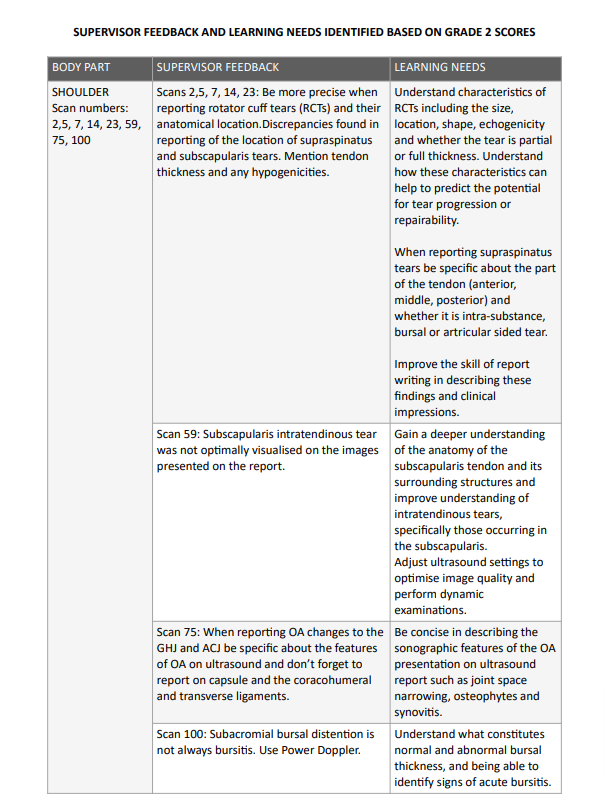

Of the 150 scans, 134 (89.33%) were recorded as grade 1, demonstrating a high level of agreement between the supervisors and the student and 15 scans (10%) were graded as 2 showing minor discrepancy, unlikely to affect patient care, finally 1 scan (0.67%) was scored 3 with potentially significant discrepancy.

The grade 2 scores could be further analysed by the anatomical area demonstrating that eight (53.33%) grade 2 scores involved shoulder; three (20%) ankle; two (13.33%) hip; wrist and foot each totalled one case (6.67% ) out of 15 grade 2 scans.

Based on the quantitative data presented the student has identified that the lower limb scans have relatively better agreement scores (average 1.06) and made up 2/3 of the case load. There was a complete agreement with knee scores (total of 27 scans) which highlights one of the strengths of the student practitioner. The others areas that resulted in in complete agreement were hamstrings

(12) , adductors (2) , calf (5), elbow (8) and hand (2) had much smaller sample size and definitive conclusions cannot be drawn.

Upper limb scans contributed to slightly over a third of the total number of scans logged and there was moderately higher number (8 cases) of discrepancies identified in the reporting resulting in grade 2 agreement score compared to the lower limb (6 cases). This indicates there were more inconsistencies in the interpretation of the upper limb scans.

5 out of the 8 shoulder scans that received a grade 2, and received a similar feedback from the supervisor, were performed at the very beginning of the mentorship programme.

The discrepancies in reporting all were attributed to the student not reporting partial thickness rotator cuff tears (RCTs) accurately based on their location and and type. This resulted in identifying a significant learning need for the student going forward.

The latter 3 scans that received grade 2 score focussed on describing the features as well as the practitioner probe skills.

Research has shown that the sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound for diagnosing partial thickness rotator cuff tears is lower (65%) than for full thickness RCTs (94%) (Cowling et al., 2017). Based on more recent literature review by Okoroha et al. (2019) suggested that ultrasound is an appropriate method for the assessment of partial thickness RCTs, however further MR imaging should be considered in the event of negative ultrasound findings if the patient continues to experience symptoms despite the conservative management. Furthermore it was reported that ultrasound may be less accurate compared to MRI to determine the tear size, tendon retraction, muscle atrophy and the degree of fatty infiltration (Okoroha et al., 2019).

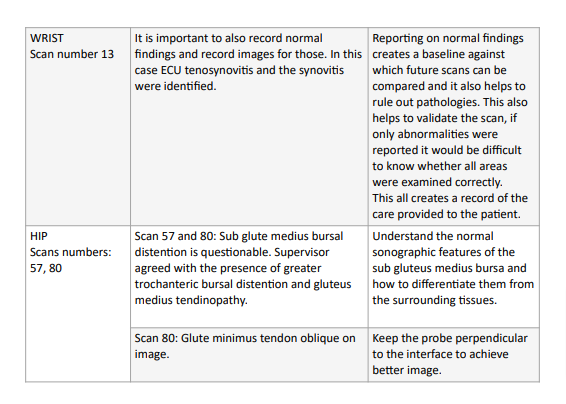

Figure 3. Tendon classification on ultrasound. Source: Hinsley et al. (2022)

A) Normal tendon on ultrasound has homogenous appearance with no abnormality;

B) Abnormal tendon with loss of homogenous appearance and ragged enthesis with or without fluid filled bursa or parLal thickness tear;

C) Full thickness tear (0-2.5cm)

D) Full thickness tear (>2.5cm): evidence of large defect or lack of tendon Lssue

More recent systematic review by Farooqi et al. (2021) demonstrated that ultrasound is highly sensitive in the diagnosis of supraspinatus full thickness tears compared to partial thickness tears. Although ultrasound was found to be highly specific for subscapularis and biceps tendon tears, the sensitivity was low due to limited number of studies available (Farooqi et al., 2021). More interestingly they found improved ultrasound accuracy of diagnosis of partial thickness tears was more prevalent in the studies between 2016-2020 compared with the studies published during 2010-2015. This could be attributed to the advances in ultrasound technology as well as improved standards of ultrasound certification programmes and standardisation of scan protocols.

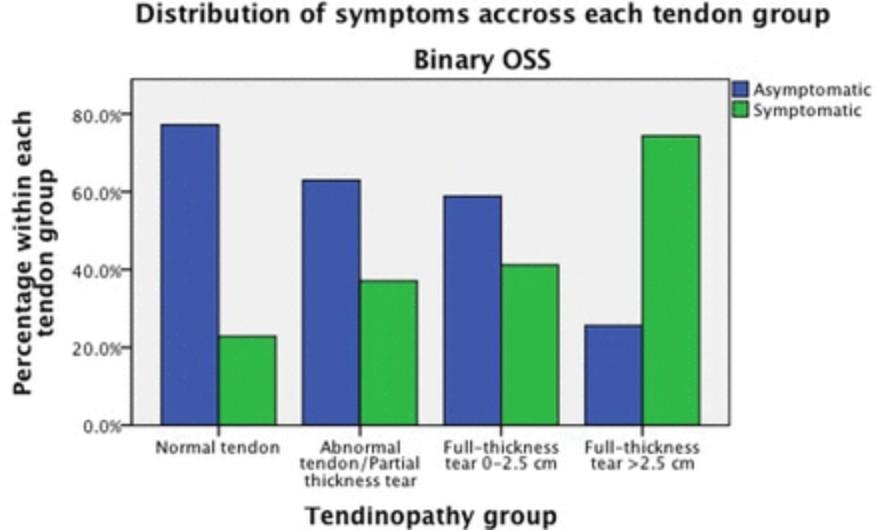

Rotator cuff tears are very common- the prevalence of full thickness tears is 22.2%, increasing with age and whether the tear being on dominant side based on the cross sectional observational study by Hinsley et al. (2022). Although 48.8% of the full thickness RCTs are asymptomatic (See Figure 4), there is an association between RCTs and patient reported symptoms and patients with at least one full thickness tear are 1.97 times more likely to have symptoms (Hinsley et al., 2022). As demonstrated in this audit the shoulder presentations in student’s clinic were the most common attributing 22.67% to the scan logbook. The student was challenged by the partial-thickness tears presenting in their clinic and because of their inexperience and lack of deeper understanding led to the discrepancies in reporting partial- thickness RCTs.

Figure 4. Source: Hinsley et al. (2022)

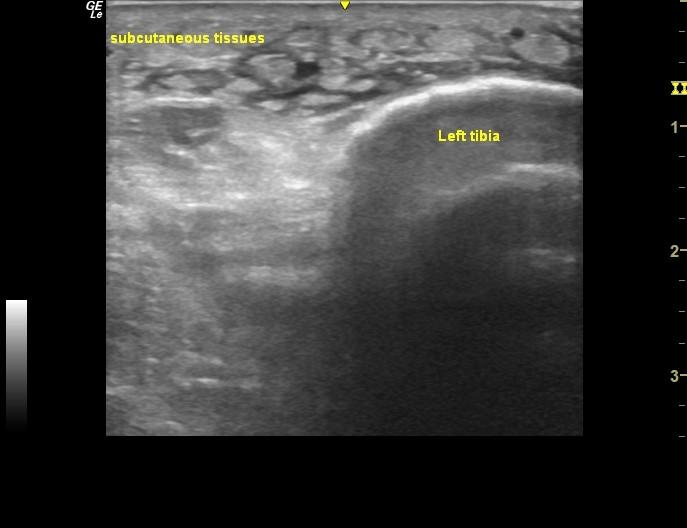

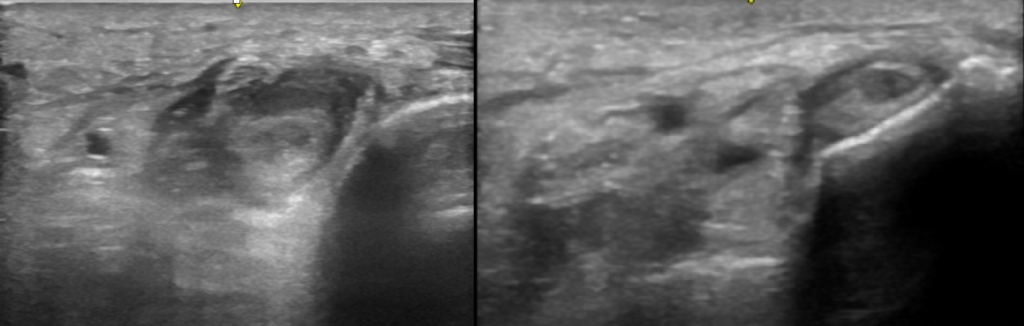

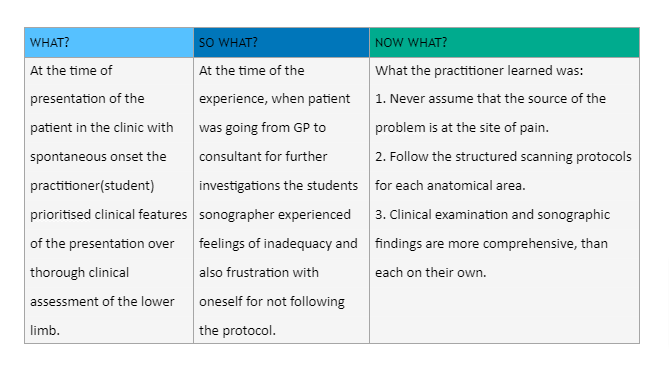

Grade 3 scan number 25 occurred following a clinical presentation of the anterior ankle pain, redness, focal heat and swelling extending upwards along the anterior aspect of the tibia, with spontaneous non traumatic onset in 76 year old otherwise active patient. Based on the clinical features and cobblestone appearance of the subcutaneous tissues on sonographic examination this case was referred on to a GP as possible cellulitis.

Image 1: Axial view of the area of maximal symptoms.

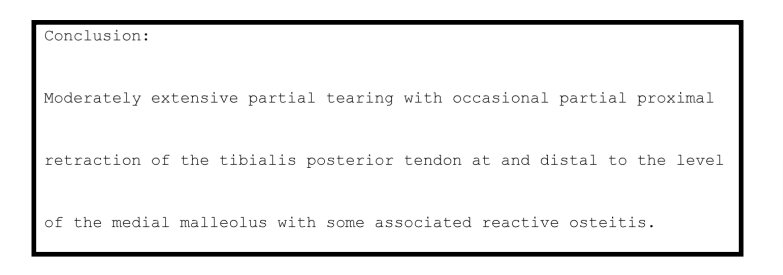

Patient received a course of antibiotics from the GP, which yield no results in resolving patients symptoms of swelling and pain in the lower limb. Further investigation was warranted, which resulted in X ray of the ankle demonstrating normal structure of the ankle followed by the MRI imaging, which reported extensive partial tears of the tibialis posterior tendon (TPT) (see Figure 5), which the student had missed.

Figure 5: MRI Report

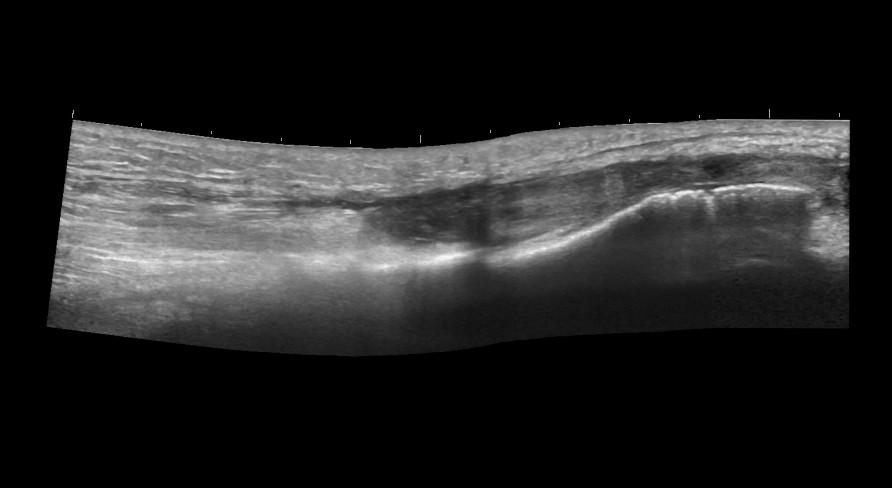

The patient was asked to attend the student clinic for a follow up scan, which helped to correlate the MRI findings with that of the ultrasound, demonstrating the loss of fibrillar pattern and mixed echogenicity of the TPT.

Image 2: Tibialis posterior in longitudinal view.

Images 3 and 4: Tibialis posterior tendon in sagittal views

A literature review by Henderson et al. (2015) showed that ultrasound has moderate to high diagnostic accuracy for the detection of a wide spectrum of soft tissue conditions such as achilles and tibialis posterior tendinopathy, peroneal tendon tears of the foot and ankle. Ultrasound is a

useful, albeit operator dependant tool, to assess the TPT as well as other soft tissue structures around the ankle. Tibialis posterior tendon insufficiency is present in up to 10% of the geriatric population (Ikpeze et al., 2019) and may be more prevalent than previously estimated. Progressive insufficiency of TPT is linked with adult acquired flatfoot deformity, a disorder caused by repetitive overloading (Polichetti et al., 2023). The prevalence of posterior tibial tendon rupture parallels the degenerative processes of aging, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity (Holmes and Mann, 1992), latter two not attributed to this presenting case.

The reason why the initial scan (number 25) was scored 3 is that the student failed to examine the ankle joint comprehensively and limited the scan to the site of symptoms. The student practitioner made further referral recognising the case presentation was out of their scope of practice, which lead to a number of further tests and definitive diagnosis. It was evident that the student identified the need for further referral and acknowledged their limitations within scope of practice in terms of diagnosing the patient condition, which ultimately led to accurate diagnosis and treatment. It was equally important for the practitioner to admit that they should have examined the ankle more comprehensively following the scan protocol and not limited the scan to the area of presenting symptoms based on clinical presentation alone.

Reporting on normal findings creates a baseline against which future scans can be compared and it also helps to rule out pathologies. This also helps to validate the scan, if only abnormalities were reported it would be difficult to know whether all areas were examined correctly.

This all creates a record of the care provided to the patient.

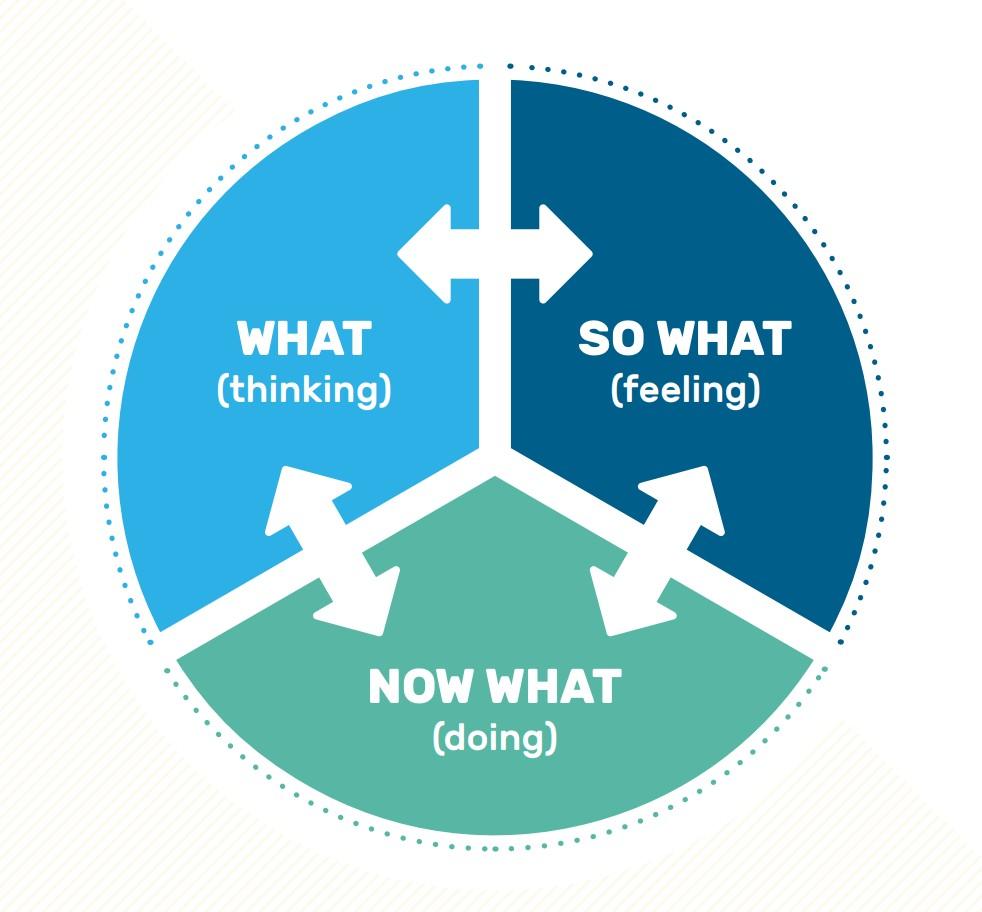

There are many approaches to reflection in clinical practice, which is a useful tool in identifying strengths and weaknesses, encouraging critical thinking about experiences and increasing self- awareness as well as professional growth. When done well it can greatly improve the skills of health care practitioner and lead to better patient outcomes (Koshy et al., 2017).

Figure 4. Example of reflective framework: What? So what? Now what? Source (GMC, 2023)

Upon reflection the grade 3 case occurred early on of the mentorship programme and whilst exploring the reasons why it occurred, a student practitioner’s inexperience and technical insufficiency has to be considered. If the ultrasound was not available in the clinic the patient would have been referred on regardless. However since the diagnostic tools were available it was a student’s oversight and failure to examine the whole ankle region comprehensively.

A number of lessons were learned from the grade 3 case as well as throughout the process of creating this logbook. The student practitioner appreciates the importance of ongoing development of probe skills as well as deep understanding of anatomy, terminology and pathology of the structures involved to be able to report accurately, which leads to better patient experience and outcome.

To address the learning needs identified during the process, in particular understanding the rotator cuff tears and their presentation on ultrasound, the student has reviewed relevant literature and engaged in case discussions with peers and mentors. The learning needs identified throughout the programme have led to the student undertake self-directed study and taking time to re-scan number of the cases that did not receive the best agreement scores.

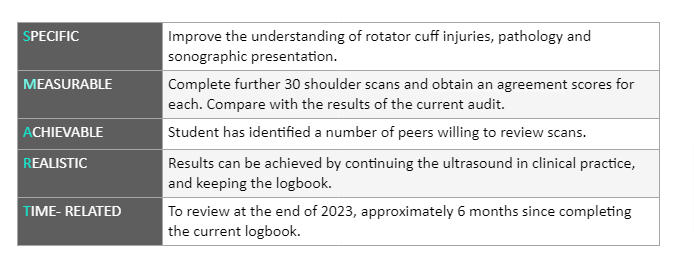

Audit is a continuous cycle that should be ongoing in clinical practice and the student is continuing their logbook and peer discussions to further develop ultrasound skills to make continuous improvements as set out in methodology, which are specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time-related.

The student has put in place the following plan to improve the diagnostic and reporting skill for shoulder pathologies, which received the highest percentage of grade 2 scores:

In order to sustain any improvements another audit cycle will be completed based on the learning needs identified and comparison made to this audit.

Clinical audit is an important quality improvement activity and has significant benefits for patients in terms of enhanced care, safety, experience and outcomes (Howlett et al., 2023). This audit highlighted specific learning needs for the student sonographer, which resulted in self directed study to understand the anatomy, sonographic features and pathology. The student will continue enhancing the ultrasound report writing skills with an aim to convey the findings by the use of standardised terminology and description of the clinical presentation. This would ultimately lead to enhanced accuracy in reporting and improvement in the quality of patient care.

These outcomes will be met through continuous self study, attending advanced ultrasound courses, practicing hands on skills and seeking feedback from more experienced peers as well as re-audit process.

The student identified their strength in evaluating lower limb, an area that the practitioner has specialist clinical interest in ever since completing their BSc is Osteopathy. It was also evident that shoulder injuries commonly present in the practice and therefore the student has put in place a plan for re audit and further self-directed study to improve their diagnostic skills when it comes to

shoulder pathology.